When a stock in a portfolio rises 500%, it’s both a blessing and a challenge. In 2025, I experienced this firsthand—my model portfolio produced a +500% winner along with six other multibaggers (three realized). My deep-dive selections also delivered a 500% return (the same stock) and I had another one sitting in my personal model portfolio. These outsized gains are exactly what systematic investors hunt for in inefficient microcap markets, but they create a practical question: does selling at some profit threshold improve or hurt long-term performance?

I ran extensive backtests to find out whether adding a ‘take-profit’ sell rule—selling any stock that rises above X%—changes outcomes. The answer may surprise readers.

When One Stock Takes Over

Big unrealized winners are great—until portfolio allocation becomes lopsided. When a single stock compounds from a 2% position to 15% of a portfolio, the dynamics change. Monthly returns become increasingly driven by that one name. The psychological pressure intensifies—every pullback feels magnified, and the temptation to “protect gains” grows.

The baseline Alpha Engineer model (with no take-profit rule) showed exactly this pattern. As of December 31, 2025, the top holding—Andean Precious Metals (APM)—represented 15.7% of the portfolio after an exceptional run. This concentration isn't inherently bad for returns, but it does create challenges for real-world investors managing their own portfolios. The concentration would be even more pronounced in a typical 20-stock portfolio. At some point, an investor may want to limit the impact of a single stock—but does doing so hurt returns? Let's find out.

The Tests

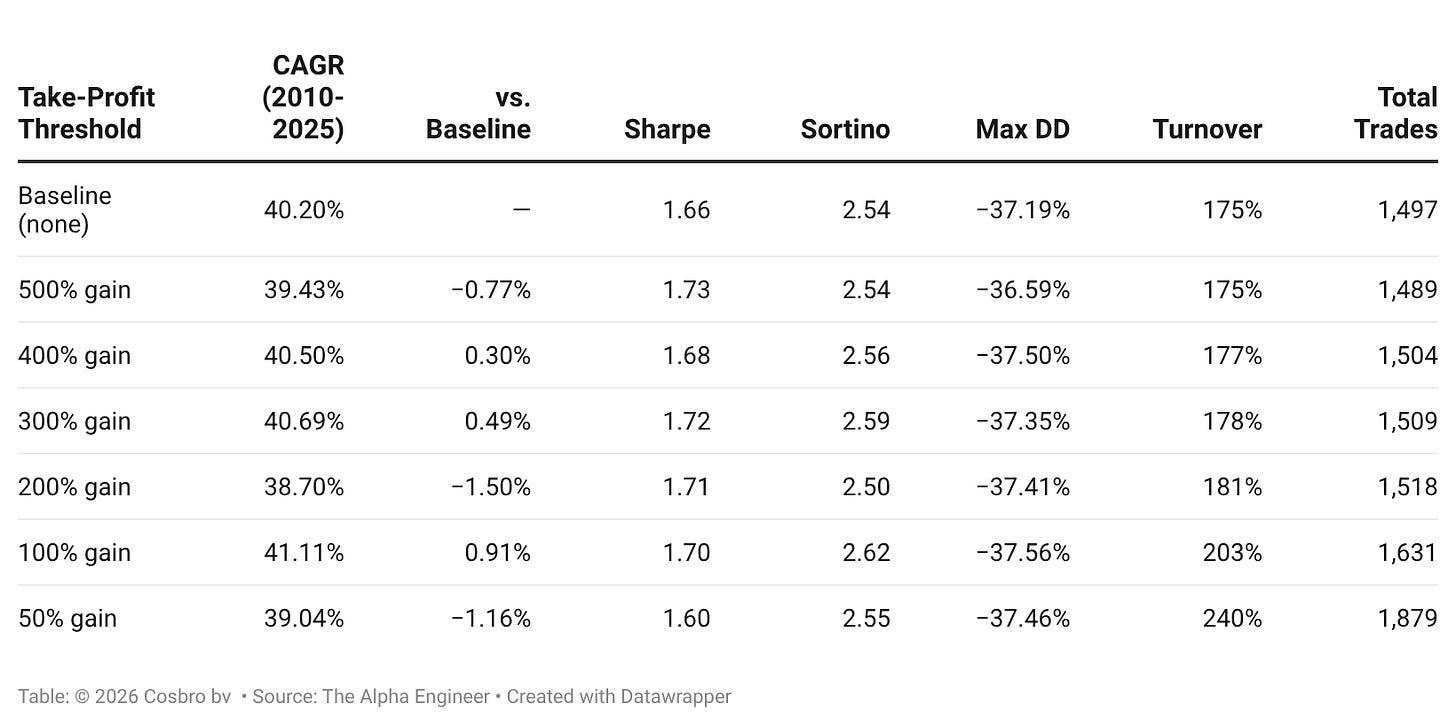

I tested six different take-profit thresholds against the baseline model: selling any stock once it rises 50%, 100%, 200%, 300%, 400%, or 500% from purchase. All other rules remained identical—the same universe with its quality filters, the same ranking methodology, and the same rank-based sell rule (exit when a stock drops below the top 10%).

The backtest period spans January 2010 through December 2025—a 16-year window that includes multiple market cycles, the COVID crash, and the 2022 bear market. All backtest reports are available for paid subscribers in the Backtest Reports archive.

The Results

What the Data Tells Us

The most striking finding is how little the take-profit threshold matters for long-term returns. Every variant—from the aggressive 50% cap to the lenient 500% cap to the rank-qualified version—delivered a CAGR between 38.70% and 41.11%. The differences from baseline range from -1.50% to +0.91%, well within the noise expected from backtesting.

Risk metrics tell a similar story. Sharpe ratios range from 1.60 to 1.75, Sortino ratios from 2.50 to 2.62, and maximum drawdowns cluster tightly around -37%. None of these variations would change an investment thesis.

The one metric that does move meaningfully is turnover. The baseline model has 174.57% annual turnover. Adding a 500% take-profit rule barely changes this (175.00%), but a 100% threshold pushes it to 202.57%, and a 50% threshold drives it to 240.46%. More aggressive profit-taking means more trading, more transaction costs, and more opportunities for slippage in illiquid microcaps.

What If Sold Stocks Get Repurchased?

One inefficiency, especially with an aggressive take-profit rule: a sold stock might still rank at the very top (rank 98 or 99) and get repurchased a week or two later when another position is sold. This creates unnecessary round-trip transactions.

To address this, I tested a refined variant of the 100% sell rule: sell at 100% gain only if the stock has also dropped below rank 98. This ensures the stock has genuinely weakened in the ranking before triggering a sale.

The result? A 40.35% CAGR—virtually identical to the baseline (40.20%) and the simple 100% rule (41.11%). Turnover dropped slightly to 198.78% (vs. 202.57% for the simple 100% rule), but the performance difference remains well within noise. Even optimizing the take-profit logic to avoid unnecessary trades doesn’t create a meaningful edge.

The Concentration Benefit

Where take-profit rules do make a difference is in managing position sizing. Look at the top holdings across variants as of December 31, 2025:

Baseline (no cap): Top position at 15.7%

500% cap: Top position at 5.1%

100% cap: Top position at 3.3%

A 300-500% take-profit rule dramatically reduces single-name concentration without meaningfully impacting returns or risk-adjusted performance. For investors who find it psychologically difficult to watch a single position dominate their portfolio, this represents a legitimate implementation consideration. For the unusual big winners (significantly above 500%), it may make sense to have a sell threshold anyway—at some point, 20-30% of a 20-stock portfolio ends up in a single name. If history is any guide, these are once-in-a-decade gains, but I hope to face this issue more often in the future!

Conclusion

After analyzing 16 years of backtested data across seven different configurations, my conclusion is straightforward:

Take-profit rules neither help nor hurt returns in a statistically meaningful way.

The choice comes down to implementation preferences:

Investors comfortable with occasional concentrated positions who want to minimize turnover may prefer no take-profit rule

Those who prefer more even position sizing and can tolerate slightly higher turnover may find a 300-500% threshold offers a reasonable balance

Thresholds below 200% meaningfully increase trading activity without improving returns

For The Alpha Engineer model portfolio, I’ve chosen not to implement a fixed take-profit rule. However, some investors may prefer to cap winners at 300% or 400% for behavioral reasons. The data suggests this is a perfectly reasonable approach that doesn’t cost returns over time.

The key insight: systematic investing isn’t about optimizing every parameter to the third decimal place. It’s about finding robust approaches that work across market conditions and sticking with them. Whether multibaggers are sold at 100%, 300%, or allowed to run further, the system keeps generating new candidates to replace them.

The Alpha Engineer --- Investing with a quantitative edge

Disclaimer: The Alpha Engineer shares insights from sources I believe are reliable, but I can’t guarantee their accuracy—data’s only as good as its inputs! This content (whether on Substack, via email newsletters, X, or elsewhere) is for informational and educational purposes only—it’s not personalized investment advice. I’m not a registered investment advisor, just an engineer crunching numbers for alpha. My opinions are my own and may shift without notice. Investing involves risks, including the chance of losing money. Past performance, whether from back-testing or historical data, does not guarantee future results—outcomes can vary. So, please consult your financial advisor to see if any strategy fits your situation. Full disclosure: I may own positions in the securities I mention, as I actively manage my own portfolio based on these strategies.